Read on for writing and course news, and for this month’s reading recommendations and poem.

Dear friends,

Oh, my first September dawn in magical, misty Mallerstang. How lucky am I?

September is a special month this year because the paperback edition of Hagitude is launched on 7th, here in the UK. And even though it’s ‘just’ another edition of a book that was first published in hardback a year ago, nevertheless every new unboxing seems miraculous to me.

As many of you will know, I grew up in a profoundly impoverished working-class family, in the far north-east of England. I was the first person in that family to go to university, and in quite a large, extended family only one person, I think, has made it to university since. People like us didn’t write books. Not many even read them, much – though I was fortunate in that my mother did. Writing was for the middle and upper classes, and in my world, if you thought otherwise, then you had ideas above your station. Who did you think you were? So although I always read voraciously, and studied both English and French literature all the way through school, it never occurred to me that one day, I might write. I wished I could, but I knew I couldn’t possibly.

I’m not entirely sure when that changed, but I think it had a lot to do with the books I read in my early twenties, when I was working for a PhD at the university of London. Every Saturday I’d scuttle down to Crouch End library on my motorbike, and come back to my bedsit with a pile of books published by Virago and the Women’s Press. Those books, all of them written by women, taught me that there were other ways of being a woman, apart from the ones I’d always been fed. They taught me, too, that there were other ways of being a woman from a working class background, and eventually I began to revel in the fact of it. I wore the badge proudly, but like the wonderful women in those unashamedly feminist books, I refused to let it define me or confine me, and in the end, it didn’t. I’m glad about that; I’m not much up for labels.

At that point, all I ever wanted to do was write – but now I wasn’t not writing because I thought women like me couldn’t – I was just very much aware of the fact that I had nothing vital to say. There was no story in me, bursting to get out. Although I could spin a good story, I had read too much profoundly psychological and philosophical literature ever to imagine that a book without something to say had any point to it at all. When, here in the UK, the new-fangled phenomenon of ‘Aga sagas’ emerged, round about the early 1990s (Joanna Trollope perhaps personifying the genre) I thought to myself that surely, writing such a thing would be easy, and I could maybe squeeze in an idea or two along the way. The typical Aga saga was once described in the Guardian as a novel which expressed ‘the nostalgic yearning for an Arcadian idyll’ – and that was me, all over. Trouble is, I didn’t know anyone who had an Aga, or was middle class, or who lived in a pretty Cotswold village. I couldn’t inhabit that world, and I couldn’t authentically write what I didn’t know. I got three pages into the first draft of some ridiculous story or other, polished it to perfection, and then realised I had no interest in pursuing it any further. I remember that there was a character who was very sniffy about summer bedding plants, and that’s about it.

When I first left corporate life and ran off to Connemara in 1994, I decided that finally, I was going to write. I envisaged a novel which would be a counterpoint to the dreadful Having It All, by Maeve Haran. Dreadful, because it made women feel that having it all – children, husband (that seemed back then to be the only option), high-flying job, social life, maybe (certainly?) even the odd lover on the side – was what we were supposed to do. Anything less was a failure. My book, burned out and hollowed out as I was from years of following the Hero’s Journey in a man’s world and trying to succeed at something I didn’t really believe was success, would be called Giving It All Away. But although I had all the fodder I needed to depict the inner and outer life of a refugee from the corporate machine, I didn’t yet have a vision of what an authentic life after burnout might be. I wrote three pages, polished them to perfection … and then realised I still didn’t have anything to say. I didn’t know what freedom actually looked like.

But oh, I still so badly wanted to be a writer. So I did something which I don’t think I’ve ever admitted to in public before. After reading an article about a woman who churned out book after book for romance publisher Mills & Boon and made a small fortune out of it, I decided that surely I could write formula fiction. I went to a secondhand bookstore and bought a lot of their books, then I sat down and wrote one of my own. (A friend of mine in Ireland at the time decided she would do the same thing. Tina, if you’re reading this, ‘fess up …) I thoroughly enjoyed writing a story to formula. I polished the finished thing to perfection, decided on a pen name, and sent it in. Not very long afterwards I received a very kind letter from the editor, who said I wrote beautifully and fluently, but she didn’t think the romance genre was for me: she wasn’t entirely sure I took it seriously. She was right, and I decided formula fiction wasn’t for me.

All the way through my six years in America, back in corporate life to fund an expensive divorce, my plan was to write a novel so that I could retire to a Montanan log cabin and channel Cormac McCarthy, writing in glorious solitude surrounded by bears and wolves. But still, I had nothing to say. Until, on my third midlife crisis, I decided to learn to fly to overcome by fear of flying – but really, to try to cure my fear of actually living. If you’ve read my first novel, The Long Delirious Burning Blue, you’ll know that I finally found something I needed to say. (And more on all of that next year, when the lovely folk at September Publishing are putting out a new edition.)

But it wasn’t all plain sailing. I’d spent my entire life reading novels, but I was having trouble constructing one. I was having trouble constructing a scene. Back in Britain, where I then was, I was lucky enough to find a mentor in popular novelist Margaret Graham, who I’d met at a writers’ event. She took some shambles of a scene that I had written and wrote it in the sort of way it would need to be written if it were in a ‘proper novel’. It was transformative: she brought the scene, and the inner world of the characters, utterly alive. And just from reading those two pages, I understood exactly how it had been done. The proverbial light bulb switched on in my writing brain, and it’s never gone off since.

That short but transformative mentorship taught me that there is a craft to being a good writer. It’s not good enough to have great ideas: you have to be able to actually write. If this sounds blindingly obvious, forgive me; I’ve come across many aspiring writers who focus all on voice and message, and find the hard work of crafting beautiful sentences, or creating compelling scenes, considerably less exciting. Me, I’m the kind of writer who loves language. It’s more than a visual, on-the-page thing; it’s more than an auditory thing, about how it sounds when you read it out loud. There’s something in a beautiful sentence that is kinesthetic. I actually feel it, in my body: it sets up some strange kind of vibration. Something happens in my gut, and something happens in my heart. I guess it’s like listening to music that moves you. And so I can read sentences by Michael Ondaatje or Janette Turner Hospital or Nicky Gemmell (in her early, less racy days) over and over again, and relish all the ways they either break my heart or make it sing.

So in answer to a question asked of me a few days ago by another aspiring writer – ‘what kind of writer do you think you are’ – I guess that’s my answer. A writer for whom the poetry of the sentence, and the beauty of the evoked image, means everything. A writer who chooses language carefully, to poke deep into the heart of things; one for whom story is far from ‘making things up’ but rather a silver-handled tool for cutting all the way through to the truth.

Wishing you all the joy and abundance of whatever season you find yourself in,

Sharon

What’s new in ‘The Art of Enchantment’ community

I’m delighted to say that I’m now officially one of Substack’s bestsellers (and have the coveted orange badge to prove it), so thank you so much to those of you who have supported this still-growing project! Here’s what’s been happening for paid subscribers during the past month:

1. My first ‘drop of enchantment’, on crafting from the land and its stories

2. A new article on concepts of Death in European myth and folklore

3. An audio file on ‘Finding Our Stories of Place’ – reflections on the archetypal imagination

4. The launch of ‘The Hearth’ – an exclusive space within ‘The Art of Enchantment’ for those who want to deepen their work with story and the mythic imagination. Membership of The Hearth includes all the benefits that paid subscribers have, but in addition there is access to four live online retreats with me each year. These retreats will last for at least two hours and will have a specific focus or theme. Like all of my work and courses, they will be focused on myth, fairy tale and narrative psychology: kickstarting the imagination, deepening our sense of belonging to the world around us, and facilitating personal transformation. Members also have access to other resources for working with the mythic imagination which I’ll offer at intervals throughout the year: audio journeys, workbooks and more.

For paid subscribers this coming month, there will be the first of a series of ‘Fairy-tale Salons’, in which I’ll provide an audio file of me reading a favourite fairy tale or short piece of mythic fiction, and then invite you to discuss it in the ‘comments’ section. My next article will be an in-depth discussion of selkies and mermaids, based on some new resources I’ve just come across. And I’m still planning the rest ...

The new Hagitude paperback is finally here!

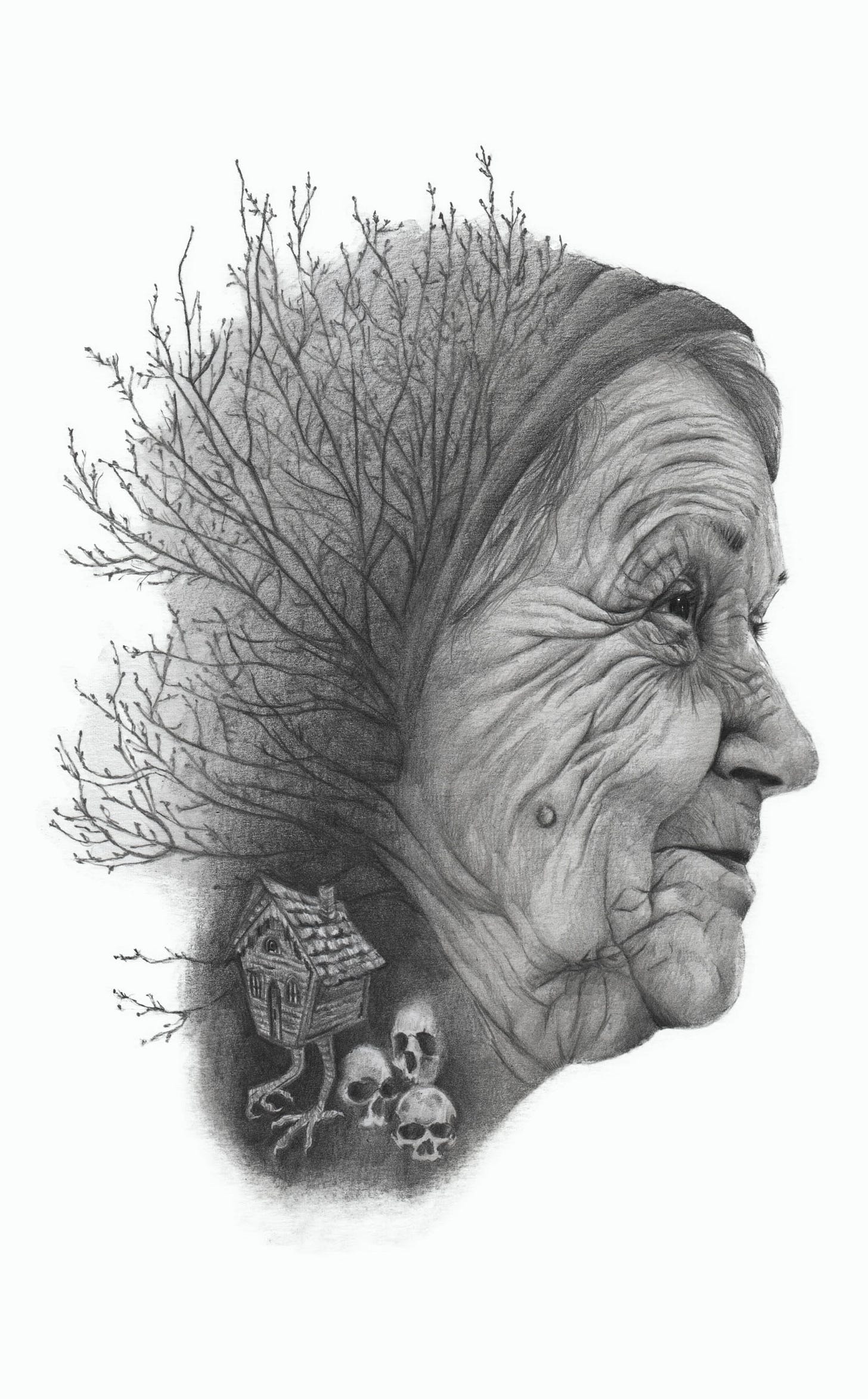

The paperback version of Hagitude will be published here in the UK on September 7, RRP £10.99, though you can find it for a pre-order price of £9.99 at Amazon UK here. This time around, we didn’t change the cover design for the paperback, but just enhanced the beautiful original. It’s still, of course, illustrated with Natalie Eslick’s beautiful images – like this one of Baba Yaga, which I think is my favourite, below.

Please head over to this page on my website and scroll down for a series of bookshop readings around the country this autumn and winter.

Upcoming Bone Cave gathering: Psyche and Eros – the Soul’s Journey Home

This autumn, I’m offering in-depth dives into two potent mythic stories. The sessions will consist of readings, teachings, breakout sessions, creative prompts, discussion, sharing, and whatever else seems appropriate at the time.

Saturday October 21, 4pm – 7pm UK time: ‘Psyche and Eros: The Soul’s Journey Home’ (£45)

In this gathering, we’ll dive deeply into the rich old myth of Psyche and Eros. Psyche is the Greek word for soul, and above all, this story is about the soul’s journey home: the soul’s journey to and through eros. In Greek philosophy, eros is described as a universal force that moves all things towards wholeness and relationship with the divine. The many tasks which Psyche has to complete on this journey – sorting, fetching the golden fleece, acquiring the water of life, a descent to the underworld – have deep resonances for us today. How can this story inform and illuminate our own journey to wholeness? What does wholeness actually mean?

We’ll also explore the relationship between Psyche and Aphrodite: the archetypical clash between Maiden and Mother.

Then, on Saturday November 25, 3pm – 7pm UK time, I’ll be offering ‘Descent: Resilience and Revelation in Catastrophic Times.’ This session will be anchored around a new visioning of Persephone’s descent to the Underworld (£60) Find out more and register here

Reading recommendations

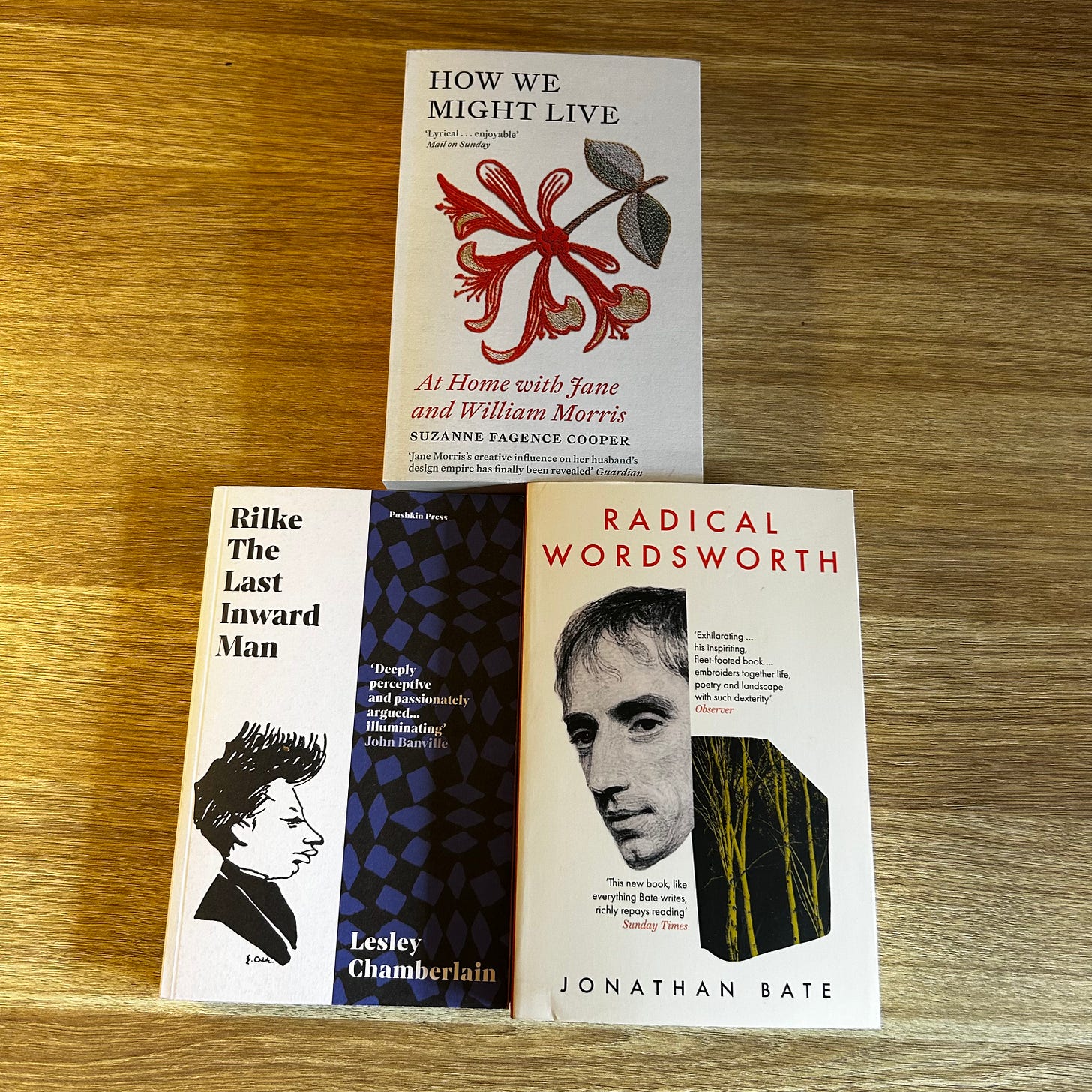

I returned from a trip to London last month carrying these three beauties, as a sign of what happens when I’m let loose in the Waterstone’s megastore in Piccadilly. (This is actually quite restrained, for me.) So far, I’m only part of the way through Suzanne Fagence Cooper’s very wonderful How We Might Live: at Home with Jane and William Morris. If you have an interest in the Arts & Crafts movement and other cultural icons of the time, this is much recommended; it’s both fascinating and inspiring. Here’s the publisher’s blurb:

William Morris – poet, designer, campaigner, hero of the Arts & Crafts movement – was a giant of the Victorian age, and his beautiful creations and provocative philosophies are still with us today: but his wife Jane is too often relegated to a footnote, an artist's model given no history or personality of her own. In truth, Jane and William's personal and creative partnership was the central collaboration of both their lives. The homes they made together – the Red House, Kelmscott Manor and their houses in London – were works of art in themselves, and the great labour of their lives was life itself: through their houses and the objects they filled them with, they explored how we all might live a life more focused on beauty and fulfilment. In How We Might Live, Suzanne Fagence Cooper explores the lives and legacies of Jane and William Morris, finally giving Jane's work the attention it deserves and taking us inside two lives of unparalleled creative artistry.

This month’s poem

Cinderella

By Anne Sexton

You always read about it:

the plumber with the twelve children

who wins the Irish Sweepstakes.

From toilets to riches.

That story.

Or the nursemaid,

some luscious sweet from Denmark

who captures the oldest son's heart.

from diapers to Dior.

That story.

Or a milkman who serves the wealthy,

eggs, cream, butter, yogurt, milk,

the white truck like an ambulance

who goes into real estate

and makes a pile.

From homogenized to martinis at lunch.

Or the charwoman

who is on the bus when it cracks up

and collects enough from the insurance.

From mops to Bonwit Teller.

That story.

Once

the wife of a rich man was on her deathbed

and she said to her daughter Cinderella:

Be devout. Be good. Then I will smile

down from heaven in the seam of a cloud.

The man took another wife who had

two daughters, pretty enough

but with hearts like blackjacks.

Cinderella was their maid.

She slept on the sooty hearth each night

and walked around looking like Al Jolson.

Her father brought presents home from town,

jewels and gowns for the other women

but the twig of a tree for Cinderella.

She planted that twig on her mother's grave

and it grew to a tree where a white dove sat.

Whenever she wished for anything the dove

would dropp it like an egg upon the ground.

The bird is important, my dears, so heed him.

Next came the ball, as you all know.

It was a marriage market.

The prince was looking for a wife.

All but Cinderella were preparing

and gussying up for the event.

Cinderella begged to go too.

Her stepmother threw a dish of lentils

into the cinders and said: Pick them

up in an hour and you shall go.

The white dove brought all his friends;

all the warm wings of the fatherland came,

and picked up the lentils in a jiffy.

No, Cinderella, said the stepmother,

you have no clothes and cannot dance.

That's the way with stepmothers.

Cinderella went to the tree at the grave

and cried forth like a gospel singer:

Mama! Mama! My turtledove,

send me to the prince's ball!

The bird dropped down a golden dress

and delicate little slippers.

Rather a large package for a simple bird.

So she went. Which is no surprise.

Her stepmother and sisters didn't

recognize her without her cinder face

and the prince took her hand on the spot

and danced with no other the whole day.

As nightfall came she thought she'd better

get home. The prince walked her home

and she disappeared into the pigeon house

and although the prince took an axe and broke

it open she was gone. Back to her cinders.

These events repeated themselves for three days.

However on the third day the prince

covered the palace steps with cobbler's wax

and Cinderella's gold shoe stuck upon it.

Now he would find whom the shoe fit

and find his strange dancing girl for keeps.

He went to their house and the two sisters

were delighted because they had lovely feet.

The eldest went into a room to try the slipper on

but her big toe got in the way so she simply

sliced it off and put on the slipper.

The prince rode away with her until the white dove

told him to look at the blood pouring forth.

That is the way with amputations.

They just don't heal up like a wish.

The other sister cut off her heel

but the blood told as blood will.

The prince was getting tired.

He began to feel like a shoe salesman.

But he gave it one last try.

This time Cinderella fit into the shoe

like a love letter into its envelope.

At the wedding ceremony

the two sisters came to curry favor

and the white dove pecked their eyes out.

Two hollow spots were left

like soup spoons.

Cinderella and the prince

lived, they say, happily ever after,

like two dolls in a museum case

never bothered by diapers or dust,

never arguing over the timing of an egg,

never telling the same story twice,

never getting a middle-aged spread,

their darling smiles pasted on for eternity.

Regular Bobbsey Twins.

That story.

From Transformations (1971)

That Cinderella! What a story! So much better than the sanitized version we grew up with. I’m grateful that you shared your journey as a writer. I’m inspired.

I love what you say about beautiful and well-crafted words. I feel the same way.