On getting over ourselves

... and on the archetype of the Philosopher, and the virtue of accepting that we don't know shit

Health warning: this article was composed by a woman who is increasingly embracing her inner curmudgeon. (Alternative terms: termagant, harridan, old biddy, battleaxe, shrew.) But do read on: it turns out nice in the end.

Dear friends,

According to a seemingly infinite array of Instagram (and increasingly Substack) influencers, ‘wisdom keepers’, ‘tradition holders’ and miscellaneous wannabe experts on this and that, what women (maybe a few men, but mostly women) should be doing today is having ‘the courage to be authentically ourselves’, trusting ‘our own feelings and perceptions’, ‘owning what we know’ (?) and assuming that ‘what matters to us, really matters to the world’.

Huh? What does any of this actually mean? That we’re supposed to push alternative sources of wisdom to one side and mistrust alternative sources of knowledge, and prioritise what we ourselves might believe, or perceive through our highly individually-variable physical senses, or deduce from often-deceptive or poorly interpreted emotional states – and in cases where those beliefs, perceptions and emotions are inevitably going to conflict with someone else’s equally valid ‘embodied truth’, or (heaven forbid) with some universally accepted measure of objective reality? I imagine then that we’re all supposed to sit around cross-legged, proudly (and probably rather breathlessly) intoning, ‘Bugger reality and bugger everyone else: I am authentically myself and own what I know and what matters to me must matter to the world by some utterly irrational process I don’t quite understand but I read a meme once so it must be true because I trust my own feelings and perceptions and this is all very courageous of me. Om, and everything.’

Do we really think we know so much? That each of us is our own perfectly turned-out discerner, our own fully formed arbiter of truth and wisdom, purely by virtue of existing? Quite apart from the fact that this all sounds intensely solipsistic as well as a recipe for anarchic chaos at every level, if we’re all supposed to be so authentically clever and embodied-ly wise, how have we managed so very thoroughly to mess everything up, and so very spectacularly to break the planet? (Ah, but I forgot: we’re not the ones who did that – it’s all the others!)

We really should get over ourselves, and admit that we haven’t got a clue. And wouldn’t it just be incredibly restful to stop wanting to impress on the world how much we know and how embodied our wisdom is, and accept instead that we really don’t know anything much at all that’s of any use? Every year of my life I learn how little I knew during the previous year, and that’s the joy of getting older, the adventure of it. I just love it. It makes me laugh. Such an attitude – as far removed as it’s possible to be from the big-bearded certainty of the prophet or preacher-man – means that I’m still open not only to growing and transforming (and always and forever learning), but to laughing at myself (which, in my book, is close to the greatest of all possible human virtues). I’m 65 this coming summer and I don’t remotely imagine I’m anywhere close to being fully formed. I’ve also trusted my ‘embodied wisdom’ before and ended up in some very deep shit, so you can be sure that although it’s very much in the mix of ‘stuff to take into account’, I’m nowhere close to imagining that it’s the most reliable of all possible sources of universal truth.

I do so very much wish that we could stop trying to impress on the world the idea that we are each the source of infinite cosmic (or at a minimum, intergalactic) insight and wisdom, the uniquely inspired teacher that the entire universe has breathlessly been waiting for, for aeons, and just admit that none of us knows shit – because if we did, we wouldn’t be so deep in it. And stop imposing our wilful little foibles on the world in the name of ‘being authentically ourselves’ and ‘trusting our truth’. If we could only just hold off on our increasingly frantic chest-beatings for a while and sit quietly in said world and pay attention, the pattern we’re fumbling for might just finally remove its fingers from its ears and slowly begin to reveal itself. But if we’re already convinced that we know it all, why would even we bother?

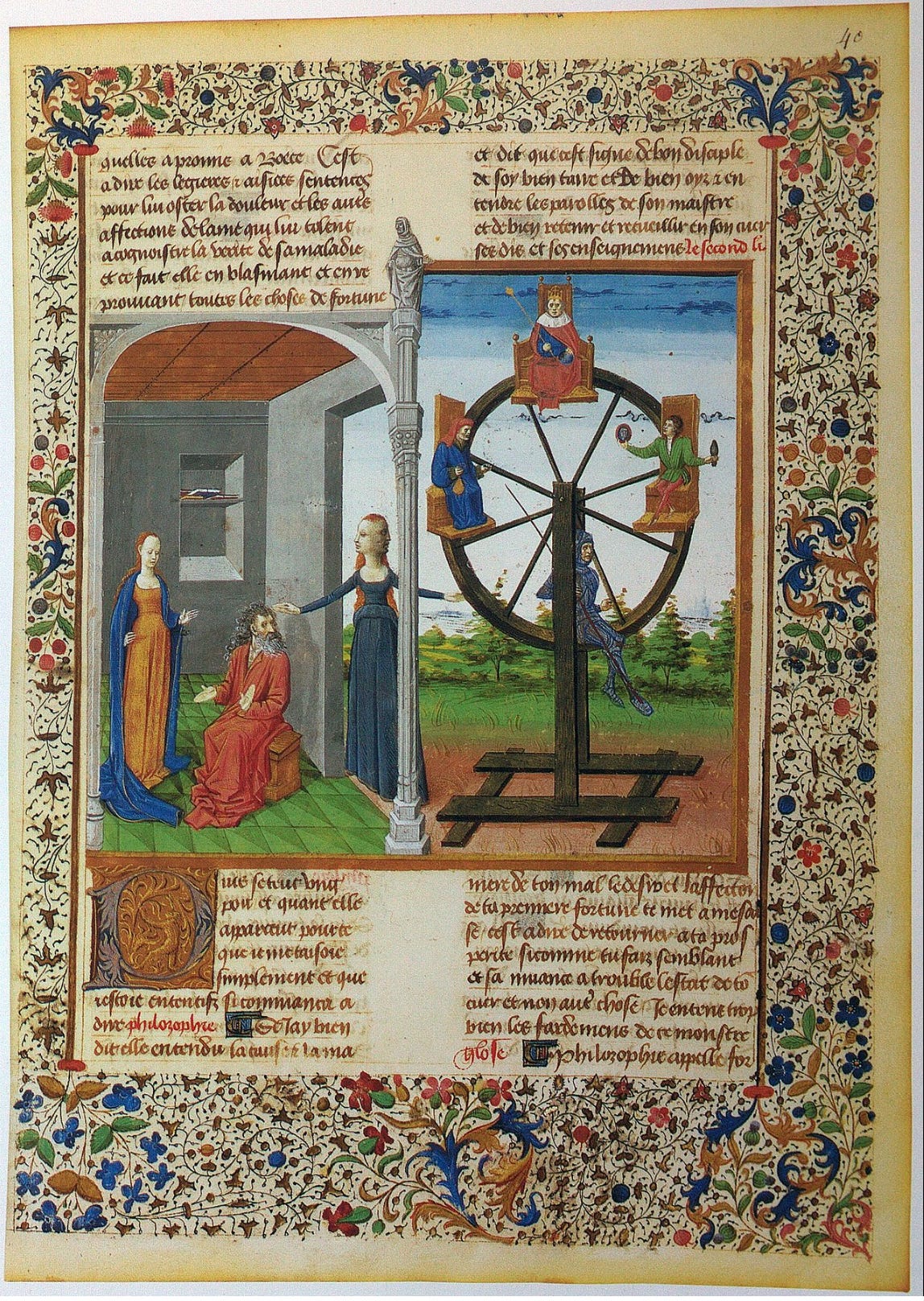

A page from a medieval French translation of Boethius’ On the Consolation of Philosophy (523 AD). One of my favourite medieval images, it (on the left) shows a decidedly big-bearded Boethius being lectured at (and patted kindly on the head – ‘There, there, Boethius; I know this is all a bit complicated, but do try to keep up’) by the very wise and wonderful Lady Philosophy, who can see in at least two directions, see at least two sides of every issue, or apply at least two varying types of knowledge to any given situation, depending on your interpretation of the character and her message. (On the right side of the image is the Wheel of Fortune. )

What would happen if we began each day from the position that we don’t know everything, and that what we proudly imagine to be ‘our truth’ and ‘our wisdom’ probably aren’t such perfect reflections of reality after all? What would happen if we began each day with the realisation that it’s entirely possible that we don’t actually know anything that really matters? If we only could cast aside all our categorical certainties, wouldn’t that make each day into a genuine adventure? Wouldn’t we be filled with curiosity, with all that childlike awe and wonder we lost such a very long time ago? Wouldn’t a day like that be so very much richer, so very much more beautiful? So very much wiser?

I’ve always believed that true growth and true transformation begin with the recognition that reality is radically different from, and vastly more interesting than, what we’ve been told to believe. Certainly, it’s radically different from, and vastly more interesting than, what we can grasp with our physical senses or ‘embodied wisdom’. And true growth and transformation is fuelled by a necessary determination to stare right into the heart of that dark abyss of unknowing and uncertainty, and come out loving it with everything we have.

Lady Philosophy offers Boethius wings, so that his mind can fly aloft. (No big beard in this one, but at least he’s on his knees.) The French School, 15th century.