Read on for book and event news, and this month’s reading recommendations. This message might be truncated by your email provider, so please think of clicking through to Substack and reading it in your browser. And while you’re there, do join the conversation and leave a comment!

Dear friends,

It’s been a long, wet winter and here in the far north of England, spring has been slow in coming. But finally, I’ve been able to plant out some potatoes and the salad seedlings will soon be out of the cold frame and into the raised bed; the February hens are in full-on laying mode and the wild garlic (up there at the top of my favourite wild plants; I chop it up into almost everything at this time of year) is in full profusion along the riverbank. But the light part of the year has its sorrows: because I’m a lucricrously early bird (normally up around 4am) it’s still very light when I go to bed and I can only properly sleep when it’s dark, which means I’m no longer able to leave my blackout blinds open, and really miss waking up in the middle of the night to catch a glimpse of moon and stars.

I’ve had to travel down to London quite a bit recently for various events, and when I was there a couple of weeks ago, I ended up in conversation with a woman of my age about the books we’d loved when we were teenagers. For both of us, proper classics like the Brontës and Thomas Hardy featured heavily: books that were on the English school literature curriculum at the time. But then there were the rather more illicit books that we stole from our mothers’ collections at home or smuggled out of the library. And for both of us, a blockbuster romantic novel from Australia called The Thorn Birds was pretty high on our list of much-loved teenage novels.

It was published in 1977, when I was 16. I’m not going to go into the plot here, which became pretty well known after a TV adaptation in the early 80s. But it’s not the plot that has stayed with me so much as the story behind the title; the author, Colleen McCullough, wrote this about it at the beginning of the book:

There is a legend about a bird which sings just once in its life, more sweetly than any other creature on the face of the earth. From the moment it leaves the nest it searches for a thorn tree, and does not rest until it has found one. Then, singing among the savage branches, it impales itself upon the longest, sharpest spine. And, dying, it rises above its own agony to out-carol the lark and the nightingale. One superlative song, existence the price. But the whole world stills to listen, and God in His heaven smiles. For the best is only bought at the cost of great pain ... Or so says the legend.

My understanding is that McCullough invented this ‘legend’, but that’s beside the point. The point is that this rather overwrought and very complicated image landed inside me like a sharp knife and has stayed with me ever since. And I think it’s because it seems to say something about that concept of calling with which I’ve become so utterly obsessed. I think it’s why I’ve been spent so many years declaring that we don’t come here to this world to be safe, but that we come here to risk everything. To risk everything to become who we truly are, and who we were meant to be. To risk everything, perhaps, for one beautiful song.

Calling, for those of you who aren’t completely au fait with the concept, has little to do with active concepts like vocation and purpose – because it’s not about doing, it’s about being. If you’re talking about what you do or about your purpose, you’re not really talking about calling. Calling has everything to do with meaning, though, and everything to do with our own unique way of expressing what it might be to be human in this world. And that heartfelt conversation with a stranger, and the memories which flooded over me as a consequence, also reminded me of another very beautiful story which also strikes me as having a lot to do with calling, and everything to do with remembering who we really are, and why. It’s called ‘The Hymn of the Pearl’, and it appears first in the apocryphal Acts of Thomas, though it is believed to predate it. What follows is the version of it that I wrote – taking it out of verse and into prose – for The Enchanted Life, along with some of the commentary I wrote about it.

The hymn of the pearl

Once there was a boy, the son of a king of kings, who lived happily in a house of great wealth and luxury. But his parents decided to send him on a journey. Equipping him with gold, silver and precious stones, they removed his clothing – the glittering robe and purple toga which he loved, and which suited him so well. And then they made a pact with him, and wrote the pact in his heart, so that he should never forget it. ‘Go west,’ they told him, ‘and bring back to us a uniquely beautiful pearl which lies on an island in the middle of the sea, guarded by a fierce, roaring serpent. This pearl is yours. If you do this, then when you return to us you may have your glittering robe again and your favourite purple toga. And you will inherit our kingdom together with your older brother.’

So the young boy travelled west, accompanied by two guardians – for the way was long and hard, and he was very young to travel it. After passing through many lands and seeing many wonders, he eventually came to the island he had been told about: an island in the middle of the sea where a fierce, roaring serpent lived. Once they had arrived safely on that island, his companions left him. And so the boy asked some questions, and discovered where the serpent made his home; and he remained on the island for a while, planning to wait until the serpent fell asleep (which he rarely did) so that he could take the beautiful pearl from him. But while he waited he became lonely and missed his family; and so when a local boy made friends with him, he shared with him the gold and silver and jewels that his parents had given him, and began to dress like him in order to better fit into his surroundings, and not to be treated like a stranger.

Although he had been warned by his parents not to eat the food of these people, most of whom were slaves, he was hungry as well as lonely, and he gratefully took their food when it was offered to him. And so it happened that, clothed in the garments of this strange country, and partaking of its food, he forgot that he was a son of kings, and began to serve the new country’s king: the king of these people, who were slaves. And he forgot the pearl for which his parents had sent him, and it was as if a veil covered his eyes and he fell into a deep sleep. So he remained for many years.

When years passed and still their son did not return home, his parents understood what must have become of him, and they brought together all of the nobles in their kingdom so that together they could make a plan to rescue him. His family wrote a letter, signed by all the nobles of the kingdom, reminding their son that he was a son of kings, and asking him to free himself from the slavery of the country where he now was – and to remember the pearl, for which he had been sent. Remember also your glittering robe, the letter exhorted him, and your purple toga, and come back to your family and your home!

The letter was given to an eagle, and the king of all birds flew west and soon found this boy who was now a man, and landed beside him as he slept. When, startled, he awoke, the eagle spoke to him and dropped the letter at his feet.

The man read the letter and remembered that he was of noble birth; and he remembered his pearl, for which he had been sent to this strange country. The veil fell away from his eyes. And so he left his room and went at once to the place where the terrible roaring serpent lived, and he sat down at its feet and set about the process of charming it. He sang and he crooned, and eventually he lulled the serpent to sleep. Once it was safely and soundly slumbering, he snatched away the pearl which lay in the centre of the spiral created by its coiling body. He cleaned his filthy clothes and set off across the sea, embarking on the long journey east.

Just as he was approaching the gates of his family home, servants came out to him, bearing the bright robe and the purple toga which once he had worn. He hardly remembered them now, for he had left his home many years ago, when he was a child – but as soon as the clothes were placed back into his hands, all of a sudden they seemed like mirrors of his true self. And so the man put on his old robes – the beautiful, richly coloured, glittering robes he had worn as a child, but which had grown along with him – and returned home, bearing the wondrous gift of the pearl which he had wrested from the terrible, roaring serpent who lived on an island in the middle of the great western sea.

~

If you’re not used to working with stories of this kind, it’s easy to become distracted by their literal content rather than seeing them as metaphors whose function is to shed light, as simply and as briefly as possible, on the complexities of the human condition. You could, for example, focus on the wealth and privilege of the prince’s upbringing and lose sight of the fact that, in story terms, this is simply a way of indicating that he was a loved and cherished little boy, and that worldly wealth is often a metaphor for spiritual wealth. This story, then, coming out of a Gnostic tradition, is usually interpreted as metaphorically reflecting a Gnostic perspective on the human condition: that we are (good) spirits lost in a world of (bad) matter, and that we are forgetful of our true origin as ‘inheritors of the kingdom of God’.

But here’s the thing about stories: they won’t be confined and they won’t be constrained. The best thing about stories is that they have lives of their own, and sometimes they conspire with you to subvert the ‘official’ meaning. So this story presents itself to me in another way.

We have indeed forgotten who we are. We’ve travelled a long way from the natural world that is our home, and the sense of enchantment which is reflected in the glittering robes and brightly coloured togas we once wore there, when we were children. We’ve all felt it: that nagging sense of something missing, something fundamentally wrong at the heart of our lives, a sense of profound disconnection from the wider world around us. We feel it in our burned-out, stressed-out bodies, in our anxiety-ridden thought patterns, in our broken and dysfunctional relationships, in the sense of futility which haunts our days, in the breakdown of communities and the increasingly frightening breakdown of social order, even in countries we’ve previously believed to be immune.

Because we have been scared, hungry and alone, we’ve adopted the customs of this new country and put on tainted clothing; we’ve come to worship a new king: a king who is a slave-maker. We’ve taken it all too literally and forgotten about the metaphor, forgotten that it’s supposed to be spiritual wealth we’re acquiring, not just more stuff. We’ve fallen asleep. We’ve forgotten where we came from, and where we truly belong; we’ve stopped believing that there is anything beyond us, maybe even that there’s something greater and worth fighting for. More than this, though, we’ve forgotten our calling: forgotten that the purpose of the journey we’re on is to discover the rare pearl which was always intended to be our unique gift to the world we’ve left behind.

It’s time to remember who we are.

From The Enchanted Life (2018)

~

There’ll be more about calling – and the things that can hold us back from it – for paid subscribers over the months ahead. In the meantime, I’m wishing you all the blessings of whichever season you’re in,

Sharon

Woman’s Hour on ageing – this Monday, 7 May

It was lovely to be invited back to BBC Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour for a third time to talk with Anita Rani about stories and why they matter – in this case, in the context of ageing. An hourlong discussion on the subject will be airing on Radio 4 at 10am this coming Monday; it was a lively and fascinating discussion, so do listen in if you can (it should also be available on BBC iPlayer afterwards). The other members of the panel were Dr Radha Modgil, who often appears on Radio 1, comedian Cally Beaton and Pippa Stacey. And there are clips about ageing from Kate Winslett, Gloria Steinem, Angela Ripon and Helena Bonham-Carter.

Mind Body Spirit Festival, London Olympia, May 27, 12.30–14.00. 10% discount

Challenge the narrative: move through menopause with vitality, creativity and vision

This is my last live event until autumn comes around – I’m taking a few months’ break – and so I’d love to see you at this late-May Bank Holiday Monday workshop around reclaiming the second half of life. You can also come and find me at the Hay House exhibition stand after the workshop, signing The Rooted Woman Oracle Deck and Hagitude too. There will also be Hagitude badges for anyone who comes to say hello! Details about the workshop here. I’m delighted to be able to offer a 10% discount on ticket sales – not just for my talk, but for any others at the festival; head over here, click on ‘get tickets’, select my workshop. Or quote the promo code SB10 when you’re checking out.

This month’s reading recommendation

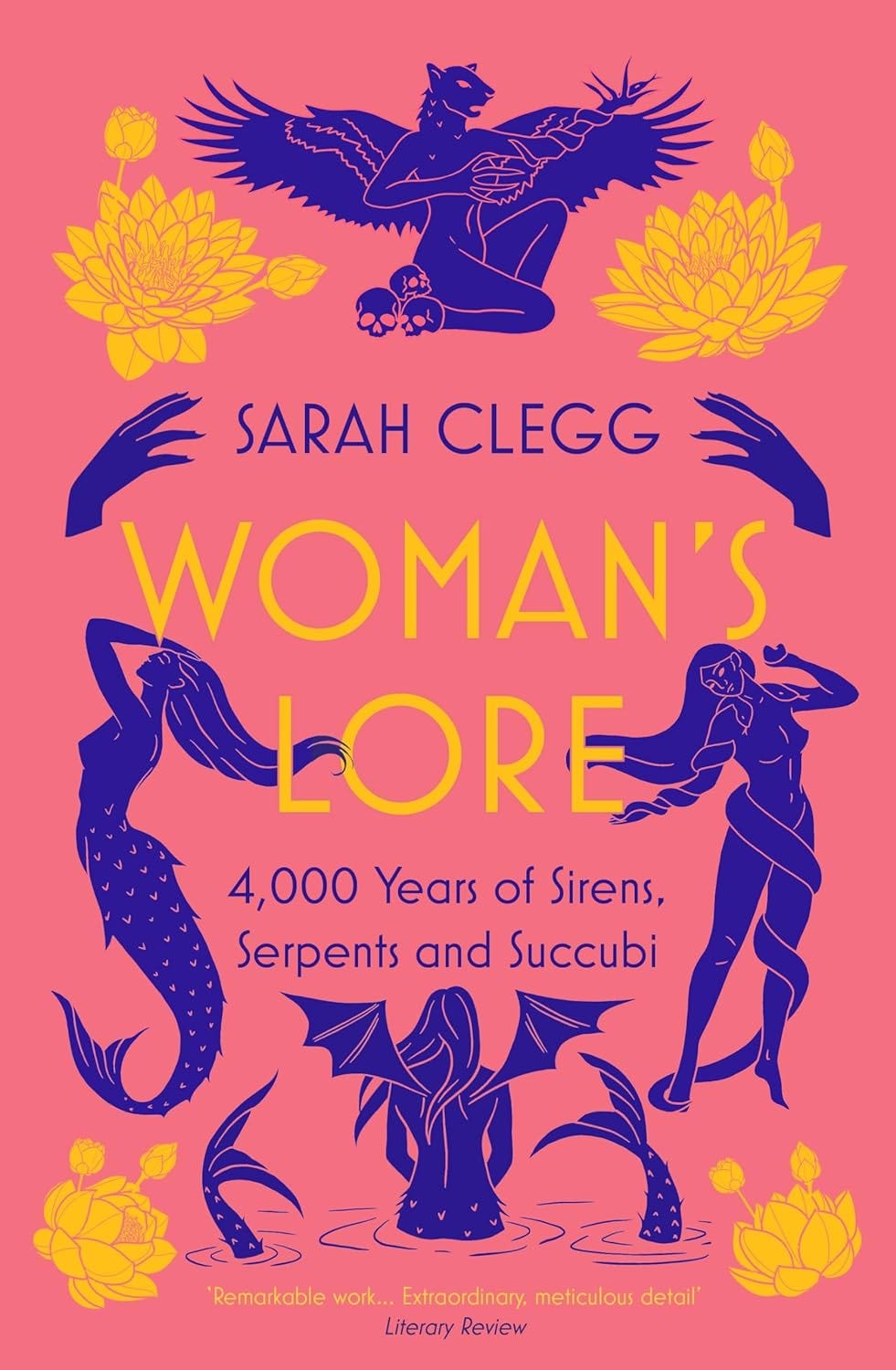

Woman’s Lore, by Sarah Clegg

Browsing at Daunt’s bookshop in Marylebone last time in was in London, I happened across this fascinating paperback. Sarah Clegg has a PhD in the ancient history of Mesopotamia from Cambridge University, and this book is about women in the mythology of ancient Mesopotamia. This is one for all who are interested in women’s mythology. Here’s the publisher’s blurb:

Shortlisted for the HWA Non-Fiction Crown Award 2023

The history of a demonic tradition that was stolen from women – and then won back again.

Creatures like Lilith, the seductive first wife of Adam, and mermaids, who lured sailors to their death, are familiar figures in the genre of monstrous temptresses who use their charms to entice men to their doom. But if we go back 4,000 years, the roots of these demons lie in horrific creatures like Lamashtu, a lion-headed Mesopotamian demon who strangled infants and murdered pregnant women, and Gello, a virgin ghost of ancient Greece who killed expectant mothers and babies out of jealousy. Far from enticing men into danger and destruction, these monsters were part of women's ritual practices surrounding childbirth and pregnancy. So how did their mythology evolve into one focused on the seduction of men?

Sarah Clegg takes us on an absorbing and witty journey from ancient Mesopotamia to the present day, encountering a multitude of serpentine succubi, a child-eating wolf-monster of ancient Greece, the Queen of Sheba and a host of vampires. Clegg shows how these demons were appropriated by male-centred societies, before they were eventually recast as symbols of women's liberation, offering new insights into attitudes towards womanhood, sexuality and women's rights.

I love this. The pearl is Divine Wisdom. Thank you for the generous offering of yours here. Extraordinary . I can’t remember where but not long ago I read pain is inevitable : suffering optional . In my season of sorrow I know this to be true. How beautiful is this song we sing as we live awake. . Being awake takes courage and sometimes challenging decisions to move in unknown directions . Hildegard Bingen talks about being a feather on the Breath of God . Feathers and Pearls. I think I might need to write.

It seems the Pearl is not the point, merely a fabricated catalyst for the initiatory journey. He forgot who he was because of the forced separation from his family and his human need to belong. He didn’t remember spontaneously but was reminded by the Eagle, sent by those who retained their memory - his Elders.

This story speaks to me of our connection to our ancestors. Of the need to be open to and aware of how they speak to us - through the world moving around us, dreams, stories, images, etc.

We can’t remember who we are without remembering to whom we belong.

Thank you Sharon for bringing forth the voices of our ancestors in these old and potent stories, for being an Elder in the sense of one who helps us retain our memory of belonging.